Testing Police Interview Techniques on mindswarms

In Making a Murderer Season 2, Kathleen Zellner observed that the detective who interviewed Brendan Dassey used the Reid Technique – an industry standard training methodology for law enforcement.

Out of curiosity, we purchased and watched the Reid Technique training series, and wondered how aspects of this methodology might apply to a mobile video interview.

Admittedly, our goals are different from law enforcement; the Reid Technique aims to gather the most truthful response from witnesses and suspects in relation to a crime. At mindswarms we aim to uncover emotional insights from consumers related to products, brands, services or advertising.

However, there are similarities between the strategies used to achieve these respective goals.

We wanted to understand how these strategies might align with best practices for collecting in-context insights for market research. And further, we wanted to identify what researchers should consider when prompting participants to give us in-context insight.

One of the Reid Techniqueʼs strategies for gathering successful responses is setting up what they define as “a proper interview environment.”

Poor vs Proper Interview Environment

According to the Reid Technique, interview environments are defined as follows:

- Poor Environment: A poor environment is characterized by multiple distractions, such as noise and interruptions. Questioning a suspect in a public place with other people around makes it difficult to develop quality information (editorʼs note: some might argue that focus groups are a “poor environment” by this definition)

- Proper Environment: A proper environment for questioning a suspect is controlled by the investigator, private, and free of distractions.

This inspired our mindswarms experiment, where we outlined two analogous prompts:

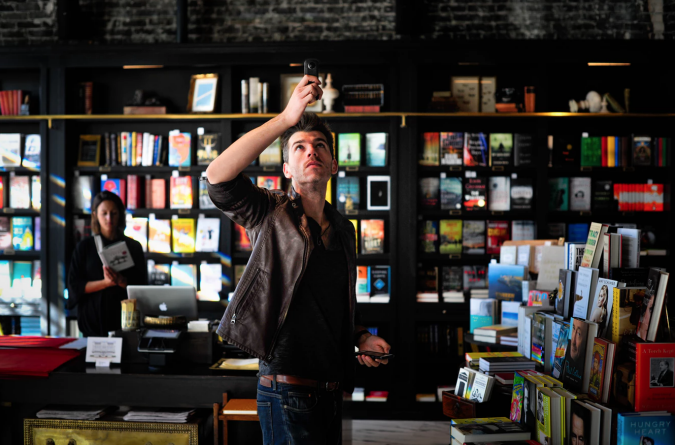

- Public Environment: One set of participants answered a personal question from a public space. This replicated the typical setting for in-context insight, and also replicated the Reid Techniqueʼs “poor environment.”

- Private Environment: A different set of participants answered the same question from the comfort of their home. This replicated a typical video diary style research prompt, and also replicated the Reid Techniqueʼs “proper environment.”

Dialing up emotion

We wanted to dial up the emotion in this parallel study, because crime is often a highly emotional topic for witnesses and suspects.

In our experiment, we prompted a personal question to research participants: “Describe a recent event that scared you, frightened you, or made you nervous. What happened?”

Half of the participants responded in a public environment and half of the participants responded from a private environment. The differences were stark.

OBSERVATION #1:

Finding a private space in public

Respondents who were prompted to record their answers from a public environment still sought out the most private space available to them. For example, finding an empty aisle at the pharmacy, a corner of a room, or a space apart from the rest of the crowd. Interestingly, people seem to intuitively seek out as comfortable of a space as possible – one free of distraction.

This may have been in part triggered by the personal nature of the question (which was by design, meant to test the extreme of a potentially emotional and deep response), but gives us insight into how participants themselves also seek out a “proper environment” to give themselves as much comfort as possible to answer thoughtfully.

OBSERVATION #2:

Darting eyes

One of the most visible body language differences between the two experimental settings was eye movement.

In public settings, participantsʼ eyes would often dart from the camera to their surroundings, showing that they were distracted. These distractions seemed to impact participantsʼ responses — they seemed less focused on the depth of their storytelling and more focused on their surroundings.

For example, watch Deniseʼs response: Denise D, Public Study

On the other hand, in private settings, participants had steadier gazes into the camera, similar to the comfortable and confident eye contact people make in one-on-one conversations. When people are instructed to respond from a private or “proper” environment, it makes it easier for them to dive deeper into the personal aspects of their stories.

See Crystalʼs response, from the comfort of her own home, where she maintains a steady gaze while telling us her story:

Crystal H., Private Study

OBSERVATION #3:

Hushed tones

Another behavioral difference between the two settings was voice volume. In public spaces, participants spoke in audibly hushed tones, another signal of their self-consciousness. For example, listen to De-Ambraʼs response — she has found a private pocket in her public setting, but speaks in a hushed tone throughout her entire answer: De-Ambra B., Public Study

By contrast, private space respondents appear comfortable and speak clearly and confidently throughout their responses. Despite the somewhat personal topic, people are quick to talk about their experiences openly when they are in a comfortable space. For example, listen to Jamesʼ tone of voice as he tells his story from a private space: James M., Private Study

OBSERVATION #4:

Factual versus Emotional storytelling

The private space respondents shared highly emotional, personal and sometimes moving stories. By contrast, the respondents who recorded in public spoke more objectively and factually about their experiences – almost as outside observers.

In the public setting, we found that even with a question that is explicitly meant to elicit an emotional response, people deferred to simply “listing the facts” and telling their stories objectively without diving into their feelings. For example:

A time that recently scared me was when I was driving home one day, and I almost got hit by a car because I was trying to move to the right lane, and I didnʼt see another car was coming. And we almost collided, and that really would not have been good. It happened so fast. To be honest, I wasnʼt really paying attention, which is probably bad too. But because of that, I could have paid for more insurance, could have had to get a new car, couldʼve injured myself. And so that time really, really scared me.

-Annette C., Public Study

In the private setting, however, participants were more unguarded and quickly opened up to describe their stories as well as explain the emotional impact those experiences had on them. For example:

This question is very hard today because itʼs a day after what made me extremely nervous and frightened. Just yesterday, there was a mass shooting in Gilroy, California. I live an hour away. I know plenty of people who were at the festival yesterday. It was very scary and I almost took my niece to the festival yesterday. Luckily, I had to work last minute and I didnʼt end up going. But it was really scary to see so many of my loved ones and friends posting about it and talking about how they were safe and luckily theyʼd left early or theyʼd gone the day before. But it was extremely terrifying and I was so anxious, having a panic attack, just making sure, contacting everyone I could, trying to gather information and make sure everybody was safe and okay and no longer there and in danger.

-Thamar L., Private Study

Private environments allowed research participants to focus on their storytelling and share on a deeper level.

Best Practices for Collecting In-Context Responses

In-context responses are a great way to measure top-of-mind reactions to stimuli in real-life settings. Mobile video is an enabler of capturing these in-context insights, but as weʼve learned in our experiment, researchers should consider the following in order to gain the most meaningful insights when sending participants on in-context missions in public settings:

- In your question prompt, provide specific instructions for where people should answer the question, considering that people will naturally seek the most private area to respond from. If youʼd like people to respond in the middle of a crowded store aisle, tell them so!

- Be mindful of what types of questions you ask in-context. While people are willing to answer questions in public spaces, it is difficult for them to dive deep into personal stories, opinions, or emotions in a public setting. In-context prompts work exceptionally well for in-the-moment responses, but personal questions are better left to a private setting in a proper environment.

- The best way to ask the deeper questions are in private settings. In order to get to a more personal level, offer private moment prompts, instructing participants to respond from their bedroom, or anywhere else they are most comfortable.

- Bookending an in-context prompt with private moments allows for a cause and effect insight. By asking a participant to describe their expectations before sending them on an in-context mission, you can set the stage and understand peopleʼs deep, existing perceptions.

- Then, by following the in-context prompt with another private moment to reflect on their in-context experience, you can understand how the experience met (or didnʼt meet) those expectations.

By using mobile video to collect responses in private settings AND public settings, researchers can effectively design studies that allow for multiple layers of insight — balancing between real time in context insights and the depth of a reflective response.

Watch a highlight reel of our experiment here:

Creative Use of Mobile Video Studies

Mobile video surveys helped us try an out-of-the-box study design, which opened up a window into what we can achieve depending on the setting of our research prompts; and how to optimize the in-context insight. With an easy way to quickly reach respondents from across the country, we were able to experiment with a simple two prompt approach and compare responses from two different types of environments. Click here for more on unorthodox and unconventional uses of mindswarms.

Have any ideas to test?

We are always looking for out-of-the-box tests to inspire our next experiment. Let us know if you have any approaches/methodologies you would like to test, and maybe weʼll make yours the topic of our next newsletter!

If youʼre interested in learning more about using mobile video for consumer insights, visit the mindswarms resource hub for free resources on mobile video ethnography, use cases, methodologies and study design.

Special thanks to the people who shared their personal stories and insights with us as part of this mindswarms study.